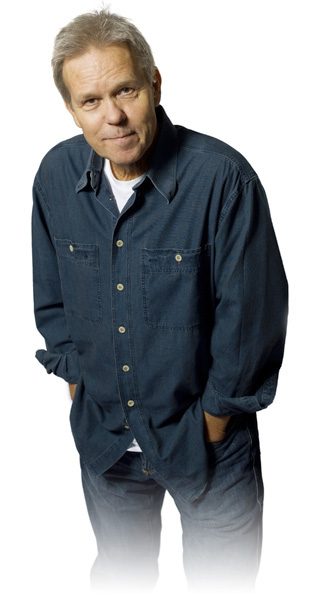

At present Mauri Kunnas (born 1950) is undoubtedly Finland’s most successful author of children’s books. To date, way over forty books of his have been published, in thirty-five languages in thirty-six countries – including Finnish and Finland –, for a total of almost 9 million copies.

His books for children have aroused enormous interest around the world. The best-known internationally is Santa Claus. It has already been translated into twenty-six languages.

Mauri Kunnas offers the reader an unparalleled joy of discovery: His brilliantly coloured illustrations are filled with rich and humorous details. He has an unrivalled gift for taking history and casting it in a new and hilarious way, as well as for giving old stories and legends his own delightful twist. And his books always exude an atmosphere which is contagiously warm and happy.

Mauri Kunnas’s first picture book was published in 1975, marking the start of his spectacular career. In his spare time, Mauri Kunnas enjoys the Beatles, playing the guitar, films and history – as well as watching thunderstorms.

I was born on February 11th, 1950 in the small town of Vammala, in the south-west of Finland, roughly 50 kilometres west of the second-largest city, Tampere. My father Martti was what is known today as a craftsman carpenter.

We lived in Asemanmäki, a district of mostly detached houses to the north of the town’s railway station. In the basement we had a complete joinery workshop, with lathes and circular saws and the whole works. When I was still a little boy, my father made toys out of wood: dolls’ prams, dogs with wheels that you could pull along behind you, and suchlike, but he moved over to making furniture when demand for wooden toys began to fade away.

I often used to mess around in the workshop, but it was obvious that I was all thumbs. I couldn’t do a thing right, and every nail I ever hammered in went crooked. My favourite tool was the file.

The toys were painted in a studio upstairs, which also served as a storeroom. The big store or warehouse that features in my first Santa Claus book – the picture that has shelves and boxes and boxes of different bits of wooden toys – is an image of our storeroom as I remember it as a kid. In the same way, Santa’s workshop has many of the features and tools I recall from my father’s workshop.

Asemanmäki had a number of workshops of various kinds, often small joinery establishments like ours, and a few rather bigger places, including a large cobbler’s workshop that eventually became a shoe factory. The dump behind it was always a great place to find amazing bits of cast-off leather. The district also had a little place that made mirrors, which in time grew to become Finnmirror, the largest manufacturer of its kind in Scandinavia. So I grew up in an environment where private enterprise was pretty much taken for granted.

We lived on the northernmost street in Asemanmäki, and right behind our house the trees started, even if you had to cross a couple of roads before you got to the really big forest. To the south the district was bordered by the railway station and the railway line that connected Tampere and the coastal towns of Pori and Rauma. We would often play down at the station, walking on the tracks and so on. Nobody ever got hit by a train in my time.

My mother Martta was at home with us until she ran the works canteen at a nearby factory. When she was working there we ate a lot of buns and donuts that were always left over from the day’s baking. My brother Matti and my sister Pirkko were both about ten years older than me, and oddly enough they still are.

My brother was brilliant at drawing, perhaps a better artist than I could be, but instead he chose to read law and he eventually became a lawyer, and he also ran the Vammala Tax Office for a time. Pirkko, too, was artistically-inclined. She was wonderful with colours. But she also had an excellent voice and in the end she became an opera singer (as Pirkko Talola).

There was no shortage of kids to play with in Asemanmäki. In the summer we’d play Cowboys and Indians and Robin Hood games in the woods. We made the weapons ourselves – after all, we did have access to all the tools in the carpentry workshop and those bits of cast-off leather from the shoe factory. My father used his band saw to make me a wooden pistol according to the design I’d drawn on paper. Then I used a knife and a file to round off the barrel and shape the grip the way I wanted it. I split a rounded piece of wood in half and nailed the two halves in place as the cylinder, and then I painted the whole thing silver. And I had myself a fine revolver! I wasn’t the only one doing this; all the boys had one. We would cut and sew pieces of leather to make our own holsters.

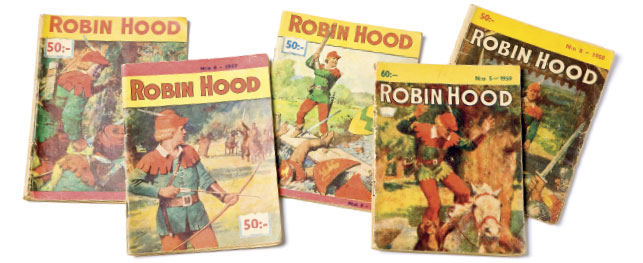

For the Robin Hood games we fashioned fine wooden swords and bows and arrows, and of course we built a treehouse camp in our own “Sherwood Forest” next door. The subjects for our other games came from comic strips, and then a bit later from TV, which was just beginning to be a household item.

The first issue of the Donald Duck comics in Finnish came out in 1951, and we had a subscription to it from 1954. Donald Duck taught me how to draw and at the same time it taught me to read. I learnt to read and write quite early. I could write my name competently enough by the time I was three, and in a way I suppose I knew how to write even before I knew properly what the letters meant. I’d ask my mother how you draw the K and so on. The Donald Duck cartoons were not by any means the only comic strips we read, and all of them were in heavy demand. I was totally infatuated with them.

We didn’t have much by way of children’s stories at home, but I borrowed books from the school library, like that Casper, Jasper, and Jonathan I already mentioned. A bit later on, Enid Blyton’s Famous Five stories were a big favourite with me.

As a child I really had no thought for “the future”. I suppose I did have some kind of fantasy image that I’d picked up from some American TV-comedy series, in which the family’s jolly Dad would draw a few advertising pictures in his study at home and then take them off “to the office”. But to be quite honest, I never believed that that sort of thing could get off the ground in Finland. So basically any drawings I made were for the desk-drawer. I suppose I imagined, like most people, that “something will come along sooner or later”.

Towards the end of my school career, our art teacher Veikko Eskola recommended that I should do like him and become a teacher of drawing. That way I’d have plenty of time left over for my own stuff. Eskola himself was also an artist. It was good advice. Even if I was clumsy and all thumbs, I was quite eager to do all sorts of “handicraft” things, though mostly out of paper. For instance I used to make my own Advent calendars, those things with the little doors that open for each day leading up to Christmas. Naturally the only big drawback with making your own calendars was that you very seldom found any surprises behind the doors – back in the 1950s we didn’t have any money to spend on sweets and things.

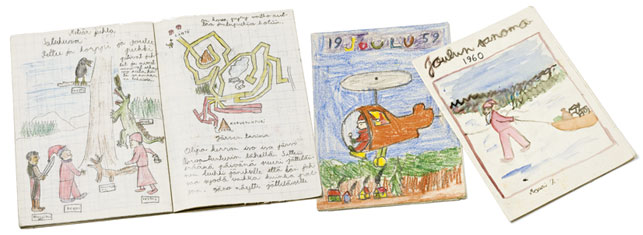

My favourite book as a little kid was Casper, Jasper, and Jonathan, by the Norwegian writer Thorbjorn Egner. Since we didn’t have the money to buy the book, I made it myself in a little notebook with blue covers. I must have been about nine at the time.

I also used to make little comic strips about the size of a box of matches. In those days drawing and sketching were a lot more common as a hobby, and a lot of my mates were rather good at it; I never thought of myself as very different from them. We used to compete to see whose comics got the most readers from among our schoolmates. I usually won. The subjects were more often than not taken from the Wild West or the adventures of the Famous Five. I was the only one of us who ended up making a career out of it.

Another thing we would make was flip-animations, the sort where you draw a slightly different picture on each page of a notebook and make it come alive by flicking the pages through with your thumb. Then we’d experiment with “rolls of film”; in other words we would draw pictures one after another on a long roll of paper and look at them on the wall by shining some kind of torch or projector through the paper and winding it between two sticks or pencils.

When I come to think of it, we made a whole load of other things, too, like decks of cards, board games, maps, all sorts of stuff.

I went to elementary and secondary school in Vammala. I graduated with my high school matriculation certificate in 1969. The grades were nothing to write home about, with an average of under 7 (on a scale of 10). I failed English, even though it was actually the only subject I thought I was any good at. As a result I had to sit the exam again and I only formally graduated in the autumn, a few months after most of my classmates. The one bright spot among the marks was the 10 I got for drawing. I don’t think that ever changed throughout my school career.

I can still remember my first art lesson very clearly. We were told to draw the night sky. Everybody laughed when I coloured the stars in as white specks. They were supposed to be yellow, apparently. I was completely dumbfounded. As far as I’m concerned they were white and they still are.

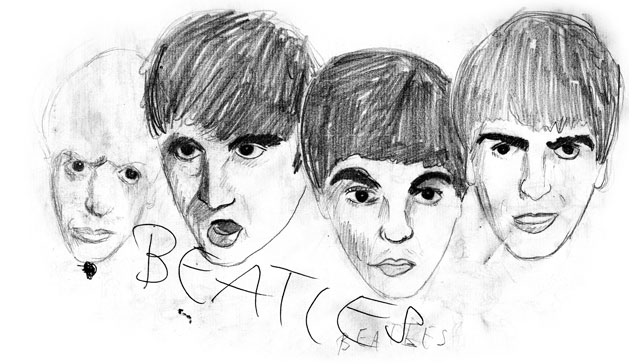

Towards the end of my school career I became a devoted Beatles fan and grew “long” hair (everything is relative). We followed the British and US pop charts almost religiously: The Who, The Rolling Stones, The Kinks, Manfred Mann, The Hollies, The Troggs, The Beach Boys, The Lovin Spoonful, Bob Dylan, Sonny & Cher, The Mamas & Papas, and Jimi Hendrix were the big names in those days. We had no time whatsoever for Finnish bands, most of whom were only doing cover versions in translation.

I took up the guitar and sang pop songs with my mates. I never joined a band at the time, even though I was offered the chance once or twice. The pages of my school notebooks were scrawled with pictures of long-haired dudes and bands. I suppose all this rubbed off in its way: nowadays I have six guitars – three electric and three acoustic. We’ve even warmed up an old band from Vammala, and I am a member. We rehearse roughly once a month – and it is great fun. We play old ‘60s covers: Stones, Beatles, and Hollies numbers, and that sort of thing.

I studied at the University of Art and Design in Helsinki, and I graduated as a graphic artist in 1975. I suppose these days it would be called a Master of Arts degree or something like that. I was bored most of the time when I was a student. I started drawing for newspapers while I was still at college: first comic strips, and then gradually political cartoons for the editorials page.

I spent a year working for an advertising agency in Turku between 1975 and ’76. When I come to think of it, that was probably the only 9 to 5 day job I’ve ever had. I’ve worked for a paper as a staff cartoonist, too, but that was rather different, and the hours were pretty flexible. From 1974 onwards I had my own daily strip cartoon in a paper called Iltaset: it was a police thing, and went under the name Kotlant Jaarti – the way Scotland Yard sounds when it is mangled by a Finn. That lasted nearly a year, and much later it was released in book form, published by the Finnish Comics Society.

At around the same time I was also drawing cartoons for Iltaset at FIM 100 a picture, but the newspaper didn’t really do very well, and that job only lasted six months or so. I think the paper eventually folded after about two years.

All the same, getting paid 100 marks a throw was pretty good money in those days, and I suspect this was one reason I got the spur to carry on with my drawing. After the Iltaset stint, I started drawing editorial cartoons for Aamulehti, which was a much bigger paper, and the main Tampere daily.

That lasted about a year, too, I guess, and then in 1975 I moved to Turku and started doing the same thing for Turun Sanomat. The move to the south-west was prompted in great measure by the fact that I’d met a wonderful local girl called Tarja. The years from 1976 to 1983 I spent as Turun Sanomat’s in-house political cartoonist. This was a very pleasant time all round. The paper’s readership liked my work, and I was often getting pats on the back for my cartoons. I liked Turku, and apparently it quite liked me. It still remains my favourite Finnish city.

At the same time as working for the paper, I was able to carry out all sorts of commissions, works for ad agencies and the like. At some point during the seven years I drew a regular weekly cartoon for Suomen Kuvalehti (a quality weekly magazine in the Time/Newsweek mould), and I think I also had illustrations and cartoons published in other papers, too.

In 1975 I had also started to draw a youth rock comic strip called Nyrok City. This was featured first in a magazine called Intro, then in Help, and finally in the popzine Suosikki. The last episodes came out in 1985 or the following year. It was a funny strip, perhaps one of the most amusing bits of work I’ve done.

In 1977 Tarja and I got married. She became a schoolteacher as well as my wife.

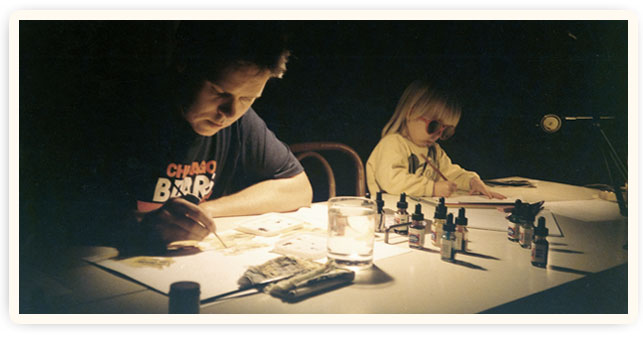

My first illustrated book for children came out in 1979. The Book of Finnish Elves was really my own experiment just to see what sort of kids’ book I could produce. My wife Tarja helped me with the colouring in of the artwork, and ever since then she has been my assistant on the subsequent books, sometimes doing more and other times taking a backseat role.

The Book of Finnish Elves was a success here in Finland. In fact I think it was probably one of the year’s bestselling titles. There was a distinct shortage of elves back then. That Christmas the newspapers all wanted to publish pictures of them and to interview me as though I was some kind of expert on the species, and so I got a good deal of free publicity.

I had my picture plastered all over the papers and, more importantly, most of the reviews were pretty favourable. There was one dissenting critic, in Aamulehti, who wrote: “If books like this HAVE to be made and published, let’s at least see that they are done properly”. Not everybody was into my elves.

In 1983 we moved to Espoo, and I was invited by Kari Suomalainen (the legendary and long-serving political cartoonist of Helsingin Sanomat) to take over from him. This was a high-profile job, but I was only there for just over a year. I eventually had to abandon doing cartoons because I found myself getting spread too thin – cartoons and writing children’s books left little time for anything else. Writing and illustrating one of these books can easily take from six to nine months, and it is quite hard work.

In the same year (1983) our daughter Jenna was born in Turku, and the business of changing diapers also ate into my working day. From around this time onwards, my publishers also rather liked me to produce a new title on an annual basis, and so I adopted this yearly rhythm.

Tarja and I produced the five books in the Ricky, Rocky and Ringo series while we were living for a while in San Francisco. They were published by the New York house of Crown Publishers.

For the Christmas market in 1996 I produced my first (and perhaps my last) animated feature film, Santa Claus and the Magic Drum. The animation work was carried out by the Hungarian studio Funny Film, with around 50 people involved on the project.

The film, based loosely on the children’s book of the same name, ran for 50 minutes and was produced by TV2 at YLE (the Finnish Broadcasting Company), who also picked up the bills. TV2 paid out around FIM 4 million in production costs, but since then I’m told the film has been sold to more than 50 countries, and it is the all-time best-selling YLE production in this respect. I even collected a YLE Export Achievement Prize for my pains.

In fact pains there were aplenty; this was so far the biggest and heaviest project I have ever got involved in. I had planned to make a second animated film, but the venture fell through because it was quite simply going to be a huge and cripplingly expensive operation. These days it can cost anything from EUR 5-15 million (or even more) to produce a full-length animated feature.

There’s really not much to complain about in the work of writing and illustrating. You can do the work when you choose, but this doesn’t mean you get by without working – deadlines have to be met, and they are seldom generous. The way of working is also a bit solitary, which isn’t always as pleasant as it might sound.

I work from home, in a studio I have downstairs. In other words, my commuting trip to and from work is approximately seven metres. Fortunately I don’t need to spend my entire time sitting alone staring at my desk, as my publishers are relatively close at hand in Helsinki. I go into the Otava offices for a cup of coffee (and naturally also for “vitally important” discussions with my editor!) at least once a week. In the summer months the family decamps to our cabin in Vammala, where I also have my own separate building in which to work.

Since we moved from Turku in 1983, we have lived in a house in the Laajalahti area of Espoo. We now have two daughters, Jenna and Noora, who was born in 1987, and a cat called Kille, who refuses to divulge his age. I’ve never had a dog, although as anyone who knows my books will tell you, I’ve also never had any qualms about drawing dogs. My parents had one, a long-haired dachshund called Rekku, but by that time I wasn’t living at home. I can’t really explain why dogs are so common in my illustrations. I tend to think of myself more as a cat person. We always had a cat when I was a kid.

When I was about five, I seem to remember that the neighbours’ rottweiler Nelly was my best friend, but as an adult I have this feeling that dogs are somehow pretty basic animals, while cats have a touch more mystery and guile to them.

The ideas for my children’s books spring up in all kinds of circumstances. Often when I’m chatting idly with people an idea will pop into my head and the light-bulb will go on, and I’ll think – yep, I could write a book about that. Just as easily ideas can come from a picture I’ve seen somewhere, on the principle that “Hey, that would look good in print”.

In most cases, however, an idea takes a good long time to develop properly. I’m quite interested, for instance, in Finnish history, and I’ve started pondering how I could work it up into a children’s book. Sometimes we have long brainstorming sessions at Otava in the search for themes for new books.

One advantage is that my wife is never short of good ideas, and she is also never afraid to clip the wings off my more outrageous plans.

My models as illustrators are mostly cartoonists. I follow closely the work of people such as Finnish cartoonist Joke Innanen, Pat Oliphant (Pulitzer prize-winning editorial cartoonist with UPS) and Jim Borgman (another Pulitzer winner with the Cincinnati Enquirer).

In the comic strip field my favourites include the late Charles M. Schulz of Peanuts fame, along with Bill Watterson (Calvin and Hobbes), and of course the great Carl Barks, who invented Scrooge McDuck and drew the Donald Duck comics through the ‘40s, ‘50s and ‘60s. I also enjoy the work of Gary Larson from Washington, coincidentally the same age as me. Larson’s Far Side drawings are a great example of how an artist who could not be called technically brilliant still manages to produce images that blow you away. From an earlier age, the British cartoonist Ronald Searle is also one of the all-time greats.

I generally tend to like artists who use a sharp brush or the pen. My Finnish favourite has always been Kari Suomalainen, and my favourite strip these days is Juba’s Viivi and Wagner, which appears daily in Helsingin Sanomat.

Even though I get to decide on my schedule all by myself, it often seems that I don’t have time to do anything much in the way of hobbies. I go to movies in nearby Tapiola whenever the opportunity presents itself. These days I mainly consume action thrillers. I adore all the old Hitchcocks and the James Bond movies. The Marx Brothers have stood the test of time well, too.

I do a certain amount of reading, though for some reason quite a bit of it seems to revolve around books about The Beatles. I guess the Fab Four count as a kind of hobby/obsession: I collect records (vinyl), and tapes with old interviews with the band and their press conferences. I’ve also been planning doing a comic-strip version of the Beatles life-history for at least a dozen years. We’ll see if anything ever comes of it. I read a fair bit of history, too, and the Viking Era in Finland and Scandinavia is of particular interest to me.

Now and then I like to read detective stories and whodunits. Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe remains my favourite sleuth. I used to devour the Agatha Christie, Quentin Patrick and Ellery Queen books, but we have them all and they’ve all been read through a dozen times and more. I still occasionally read Ian Fleming’s 007 novels, and I’ve always had a soft spot for Sherlock Holmes. Comic books I hardly ever read these days. When I was younger I would go through the old Donald Ducks and Tintin and Asterix and Lucky Luke albums, but now I can’t seem to get into them.

I don’t watch much television, but I do tape some of the English drama series, which we tend to watch at the end of the evening. I usually can’t be persuaded to sit in front of the box in the early evenings, and prefer to work instead.

I’ve also started to get very interested in genealogical research. I guess it’s approaching old age that does it. Tracking back through my family has also given me an insight into Finnish history.

Hmm… I said a few paragraphs ago that I don’t have much time for hobbies, but now it looks as though I have plenty of them! Still, my most important hobby remains my drawings and making up the stories to go with them – and that’s also my work. I must be a lucky dog to be able to mix the two.

Mauri K.